I’ve gone through a lot of computers since I got my first for Christmas in 1982 (age 10). A few were PCs. Of the PCs I’ve owned, one had a particularly interesting feature that I’ll wager no one reading this has ever heard about.

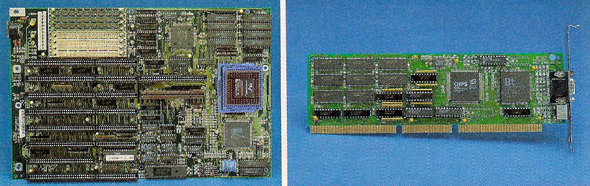

I’d been a NeXT fan since the Cube was announced back in ’88, and long lusted for their hardware. It wasn’t until ’94 that I had the opportunity to buy a NEXTSTEP box. After much research, I went with a 66MHz 486-based PC fabricated by a company out of Alaska called eCesys. The system was all black: black mini-tower case, black keyboard, black 17″ Altima screen – reminiscent of NeXT’s own black hardware. It was a thing of beauty and cost at the time, as I recall, about $4,500. Inside was a JCIS (JC Information Systems Corp.) motherboard featuring ISA, VLB, and a third bus that made it rather unique. Next to the VLB slot was a WINGINE local bus slot.

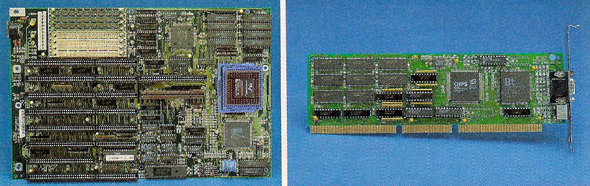

WINGINE was designed by Chips & Technologies to be an extremely high speed framebuffer requiring motherboard support in the form of a C&T chipset and a proprietary local bus WINGINE slot into which the WINGINE graphics board was inserted. This made the system one of the preferred graphics configurations for NEXTSTEP, as the operating system did not employ any 2D graphics acceleration – all it wanted was an extremely high bandwidth video subsystem. (Graphically intensive NEXTSTEP was the first OS to feature “solid drags” of windows which, at the time, was a rather heavy lift.)

The following is an excerpt from SmartComputing’s Jan. ’93 article, “CHIPS And Technologies’ WINGINE: Giving Windows Horsepower” (via Internet Archive):

A motherboard with the WINGINE chip incorporates the benefits of a local bus with another advantage–video components right on the motherboard. WINGINE Product Manager Carlos Bielicki says, “The main components of a video adapter are the graphics controller and video memory. In the WINGINE system, the ‘graphics controller’ function is carried out by the CPU and WINGINE.” Now the microprocessor has direct access to system memory as well as the video memory–without a trip to the ISA bus.

The WINGINE also utilized expensive, dual-ported VRAM as opposed to cheaper DRAM for optimal speed. I can attest to the performance delivered by the system; that black 486 truly felt like a graphics workstation. An interesting piece of technology history.

UPDATE [Feb 14, 2007]: Scott Cutler, one of the architects of the Wingine and a driver of the program, happened upon this article shortly after it was published, and shared some memories of the technology brought by the Wingine system down in the comments.

UPDATE [May 11, 2020]: I ran across another mention of the Wingine and its level of innovation in digging, online, into some specifics of the VESA Local Bus (though, the Wingine used its own proprietary local bus) in the May 18, 1992 issue of InfoWorld.

…Unfortunately, although motherboard manufacturers have their act reasonably together, graphics board and silicon manufacturers don’t. The reason for this boils down to throughput again. Current generations of graphics silicon were designed to handle only a limited amount of data per second, all piped through the graphics silicon into the graphics display memory. Local bus will require all silicon manufacturers to redesign their architectures so data transfer into graphics memory are unimpeded by wait states of any sort. The result is that transfer rates are maximized. Only Chips & Technologies has implemented this to date in its Wingine product.